Toward a systems model of CS enrolments

This term, I’m taking my supervisor’s grad course on “Systems Thinking for Global Problems“. It’s been quite interesting so far. In our last couple of lectures, we have been talking about feedback loops.

And with that on my mind, I was particularly struck by a recent post on Mark Guzdial’s blog reposting a keynote by Eric Roberts:

[in response to increasing CS enrolments], 80% of the universities are responding by increasing teaching loads, 50% by decreasing course offerings and concentrating their available faculty on larger but fewer courses, and 66% are using more graduate-student teaching assistants or part-time faculty. […] However, these measures make the universities’ environments less attractive for employment and are exactly counterproductive to their need to maintain and expand their labor supply. They are also counterproductive to producing more new faculty since the image graduate students get of academic careers is one of harassment, frustration, and too few rewards.

Computer science departments have, for decades, had cyclical enrolment. The sort of oscillation in enrolments is exactly the sort of thing you see in systems analysis when you have a balancing feedback loop with a delay in it.

Balancing Feedback Loops

Causal loops are used in systems analysis to show the relationship between variables in a system. If the variable _x_ increases when _y_ increases, and _x_ decreases when _y _decreases, they have a positive link. If, however, _x_ increases when _y _decreases, and _x_ decreases when _y_ increases, they have a negative link.

Let’s say we put a bunch of variables in a loop. If there’s an even number of negative links, then we have a reinforcing feedback loop: the system will increase (or decrease) exponentially until it hits some limit to growth. The negative links cancel each other out – so everything just reinforces everything.

But what if we have an odd number of negative links? The system tends towards an equilibrium – either it will asymptote to some value, or, more often, it will oscillate. Something will increase, another thing will decrease it, another will increase, and so on.

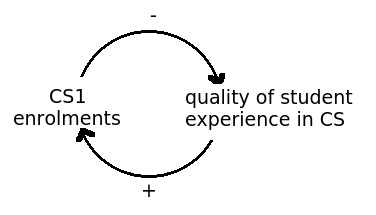

Consider:

As the number of students enroling in CS1 increases, the quality of student experience in a CS programme goes down for the reasons Eric Roberts covered above. And as the quality of the student experience goes down, the CS enrolments go down.Eventually, enrolments and my abstract “student experience” will reach equilibrium – but it won’t be a static one. The enrolments will oscillate due to delay in the system: when CS enrolments increase, the quality of “student experience” won’t go down for a while yet, and “student experience” won’t immediately affect CS enrolments.

### Playing with the Model

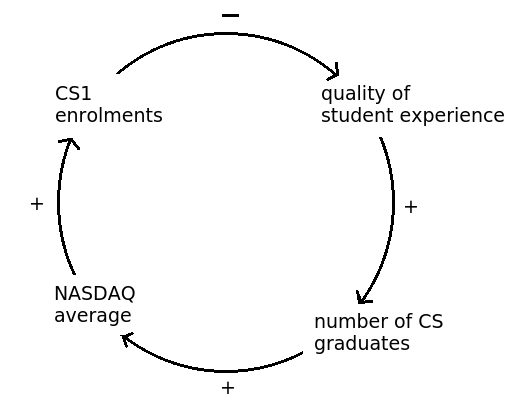

Where do CS1 enrolments come from? Eric Roberts has elsewhere observed that CS1 enrolments at Stanford (and elsewhere) are positively correlated with the NASDAQ average – with some delay.

And with some delay, one would think (hope?) that the number of computer scientists in the economy would increase the NASDAQ average. Again, a balancing loop emerges with some delays in it:

Let’s think some more about the relationship between CS1 enrolments and the number of CS graduates.

The more CS1 enrolments there are, the more students in a CS department relative to the number of CS professors. Let’s call that “students / profs” for short.

As students / profs increases, the use of sessional lecturers increases. The number of courses a department offers decreases – which in turn decreases the amount of streaming in CS programmes. The teaching load for faculty increases, in turn hurting faculty satisfaction.

Even with the abstract “student experience” unpacked somewhat, we still see a balancing feedback loop. It doesn’t matter what path you take from “students/profs” to student retention – there’s an odd number of negative links.Now, everything so far has assumed the number of faculty is fixed. But it’s not quite – with a (often substatial) delay, increased enrolments will lead to more faculty hirings. Let’s look a bit more at that:

Here we have our first reinforcing loop. The more students/profs, the more the teaching load – and down goes faculty satisfaction, more profs quit and go into industry, and then the ratio of students/profs gets even worse.

This feedback loop would continue on until it hits a limit to growth (no faculty to teach classes?) if it weren’t for the interacting effect of faculty hirings. The more faculty leave, the more faculty need to be hired. If we ignore our link between faculty turnover and the number of faculty, what we have here is a balancing feedback loop: profs who leave are replaced, and all is steady.

What could change that is university funding for hiring more faculty above the replacement rate. This is going to be institution-specific, so it’s hard for me to come up with a model here. (Even for any given institution, funding structures tend to be incredibly complicated.)

As I’ve been playing with these models, it’s striking me that it’s unlikely the cyclical enrolments in CS will stop. For them to stop, we’d have have either a nice steady tech economy – meaning interest in CS was steady – or we’d have to have a university funding structure where faculty can be rapidly hired in proportion to increasing enrolments.

Any ideas on how the models could be refined – or leveraged? This is just a first stab at modelling this. Let me know in the comments.