What CS Departments Do Matters: Diversity and Enrolment Booms

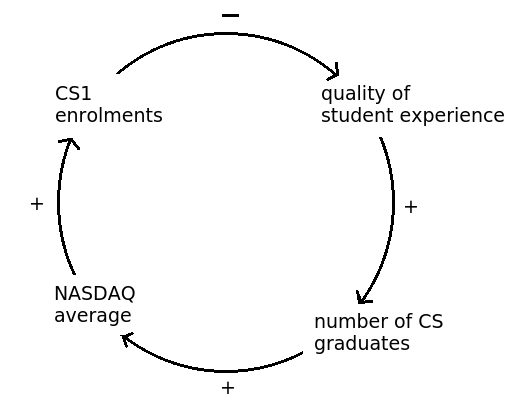

I’ve written before about the historical factors that have led to the decline in the percentage of women in CS. The two enrolment booms of the past (in the late-80s and the dot-com era) both had large impacts on decreasing diversity in CS. During enrolment booms, CS departments favoured gatekeeping policies which cut off many “non-traditional” students; these policies also fostered a toxic, competitive learning environment for minority students.

We’re in an enrolment boom right now so I — along with many others — have been concerned that this enrolment boom will have a similarly negative effect on diversity.

Last year I surveyed 78 CS profs and admins about what their departments were doing about the enrolment boom. We found that it was rare for CS departments to be considering diversity in the process of making policies to manage the enrolment boom.

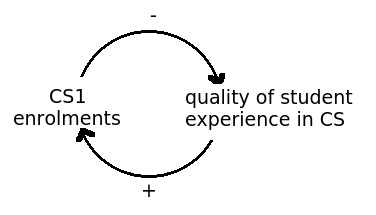

Furthermore, in a phenomenographic analysis of the open-ended responses, I found that increased class sizes led many professors to feel their teaching is less effective and is harming student culture (this hasn’t been published yet — but hopefully soon!)

Around the same time I put out my survey, CRA put out a survey of their own on the enrolment boom. Their report has just come out; they have also found that few CS departments are considering diversity in their policy making — and that the departments who have been considering diversity have better student diversity.

The Relationships Between Unit Actions and Diversity Growth

The CRA Enrollment Survey included several questions about the actions that units were taking in response to the surge. In this section, we highlight a few statistically significant correlations that relate growth in female and URM students to unit responses (actually, a composite of several different responses).

1. Units that explicitly chose actions to assist with diversity goals have a higher percentage of female and URM students. We observed significant positive correlations between units that chose actions to assist with diversity goals and the percentage of female majors in the unit for doctoral-granting units (per Taulbee 2015, r=.19, n=113, p<.05), and with the percent of women in the intro majors course at non-doctoral granting units (r=.43, n=22, p<.05). A similar correlation was found for URM students. Non-MSI doctoral-granting units showed a statistically significant correlation between units that chose actions to assist with diversity goals and the increase in the percentage of URM students from 2010 to 2015 in the intro for majors course (r=.47, n=36, p<.001) and mid-level course (r=.37, n=38, p<.05). Of course, units choosing actions to assist with diversity goals are probably making many other decisions with diversity goals in mind. Improved diversity does not come from a single action but from a series of them

2. Units with an increase in minors have an increase in the percentage of female students in mid- and upper-level courses. We observed a positive correlation between female percentages in the mid- and upper-level course data and doctoral-granting units that have seen an increase in minors (mid-level course r=.35, n=51, p<.01; upper-level course r=.30, n=52, p<.05). We saw no statistically significant correlation with the increased number of minors in the URM student enrollment data. The CRA Enrollment Survey did not collect diversity information about minors. Thus, it is not possible to look more deeply into this finding from the collected data. Perhaps more women are minoring in computer science, which would then positively impact the percentage of women in mid- and upper-level courses. However, units that reported an increase in minors also have a higher percentage of women majors per Taulbee enrollment data (r=.31. n=95, p<.01). Thus, we can’t be sure of the relative contribution of women minors and majors to an increased percentage of women overall in the mid- and upper-level courses. In short, more research is needed to understand this finding.

3. Very few units specifically chose or rejected actions due to diversity. While many units (46.5%) stated they consider diversity impacts when choosing actions, very few (14.9%) chose actions to reduce impact on diversity and even fewer (11.4%) decided against possible actions out of concern for diversity. In addition, only one-third of units believe their existing diversity initiatives will compensate for any concerns with increasing enrollments, and only one-fifth of units are monitoring for diversity effects at transition points.

From a researcher’s perspective this has me happy to see: we used very different sampling approaches (they surveyed administrators, I surveyed professors in CS ed online communities), we used different analytical approaches (their quantitative vs. my qualitative), and we came to the same conclusion: CS departments aren’t considering diversity. This sort of triangulation doesn’t happen every day in the CS ed world.

CRA’s report gives us further evidence that CS departments should be considering diversity in how they decide to handle enrolment booms (and admissions/undergrad policies in general). If diversity isn’t on policymakers’ radars, it won’t be factored into the decisions they make.